From the Attention Economy to the Story Economy

Last weekend, right before the snowstorm that hit much of America, my wife and I joined a Robert Burns’ Night gathering in our neighborhood. Celebrating the national bard of Scotland, the evening ended with friends and strangers reciting Burns’s poetry and offering up poems, songs, and literary reflections of their own. Each small performance felt like a response—direct or indirect—to the larger context beyond the living room.

Watching this show of sorts, I found myself thinking: this is as real a cultural event as any other I’ve been to recently.

As we enter 2026, it feels like the right moment to ask a deceptively simple question: How are we going to participate?

Not just as arts patrons or culture consumers — but as audiences, creators, and humans living inside a number of shared stories and spaces. And in this political moment, why does participation still matter?

For a long time, participation felt intuitive. We went out. We showed up. We sat next to strangers. We argued on the walk home. A lot of this cultural participation took place in public. These forms of participation have not vanished, but in some circumstances, they have become harder — more expensive, more effortful, more demanding. This shift isn’t just about theatre or cinema; it reflects a broader change in how we move through public life. That matters, not because it excuses disengagement, but because it changes where and how stories are encountered.

From Attention to Story

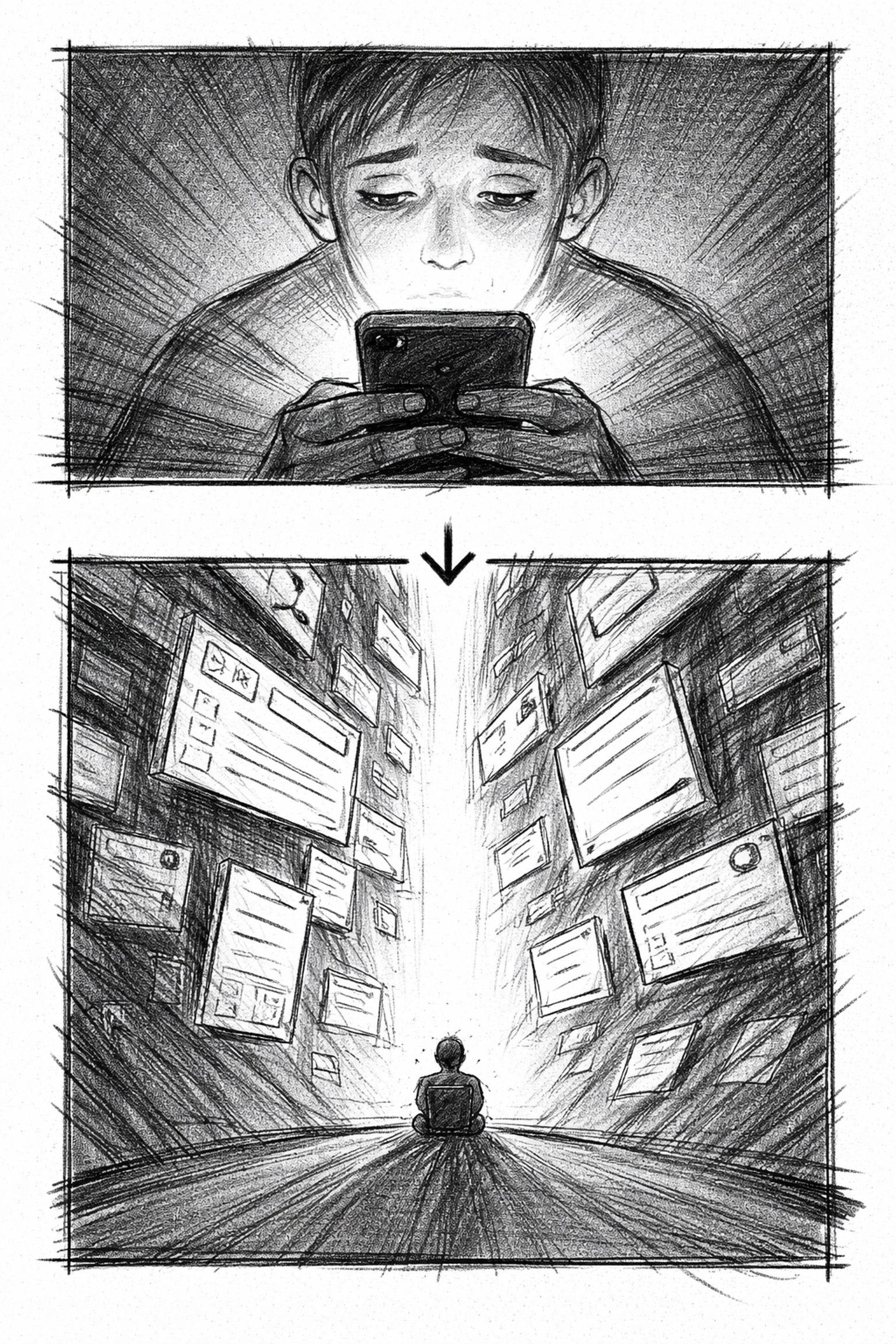

Much has been written about the “attention economy”: how our clicks, views, and time spent are harvested, packaged, and sold. In this model, the goal isn’t understanding — it’s engagement. Volume matters more than context. Reaction matters more than reflection.

But attention alone doesn’t explain how meaning is made. I’d like to suggest we reframe this “attention economy” as a “story economy” — one in which the stories that circulate most freely don’t just capture attention, but actively frame reality. They shape what feels normal, what feels dangerous, what feels inevitable. In a story economy, control over narrative is a form of power. And the stories that spread fastest are often not the most accurate or humane, but the most legible, provocative, and emotionally efficient.

What often gets missed in this framing is the role art plays inside that economy.

Art doesn’t compete with the news. It undergirds it. Artistic stories: plays, films, novels, songs: create the deeper context through which the constant onslaught of news is interpreted. They slow time. They complicate cause and effect. They train us to hold contradiction, ambiguity, and multiple perspectives at once. In a story economy, art provides the long view that news alone cannot.

Public discourse, after all, isn’t a single conversation. It’s a state made up of many smaller ones, sometimes overlapping, contradicting, and informing one another. These conversations take place at kitchen tables, in classrooms, in group chats, on major networks and massive screens, in tiny theaters, and on the largest stages in the world.

When we stop participating in the discussion — at any level — we don’t opt out. We cede the space.

Stories are the currency of culture. Consider the recent shootings in Minneapolis, in which federal ICE agents killed members of the community. Almost immediately, competing narratives emerged: framed by some as justified defensive acts, by others as unnecessary uses of force, and by neighbors and activists as another chapter in a longer story about power, visibility, and whose lives are treated as expendable. These distinctions — fact, fabrication, moral fable — are not abstract. They are how meaning is made in real time.

Now consider Hamilton, which reframed a national narrative about America’s founding through rhythm, casting, and voice. Or Adolescence, which unsettles assumptions about responsibility by refusing a single, clean truth in favor of overlapping perspectives.

In the story economy, narratives move faster than verification. Emotional clarity often beats complexity. Stories don’t just describe reality. They organize it. To state it plainly, the stories we share through art — those read at Burns’ Nights, performed in your local theatre, supported by organizations like The Orchard Project — they have an essential role to play in supporting, challenging, questioning, inspiring, and even distracting us during these wild times. They provide us with the foundational vocabulary and moral/emotional references that enable us to process current events and public discourse.

Why This Matters

In a story economy, absence isn’t neutral. When we don’t recognize what kind of story we’re encountering — and who is doing the framing — we surrender agency over meaning. Faster, simpler narratives fill the void, not because they’re truer, but because they’re louder.

So, my question for 2026 is not whether or not stories will shape our culture. They already do. The question is whether we will participate in telling and shaping these stories — or quietly hand that power to others.

Leave a Reply