Looking Them in the Eye: The Art of the Direct Address Opening

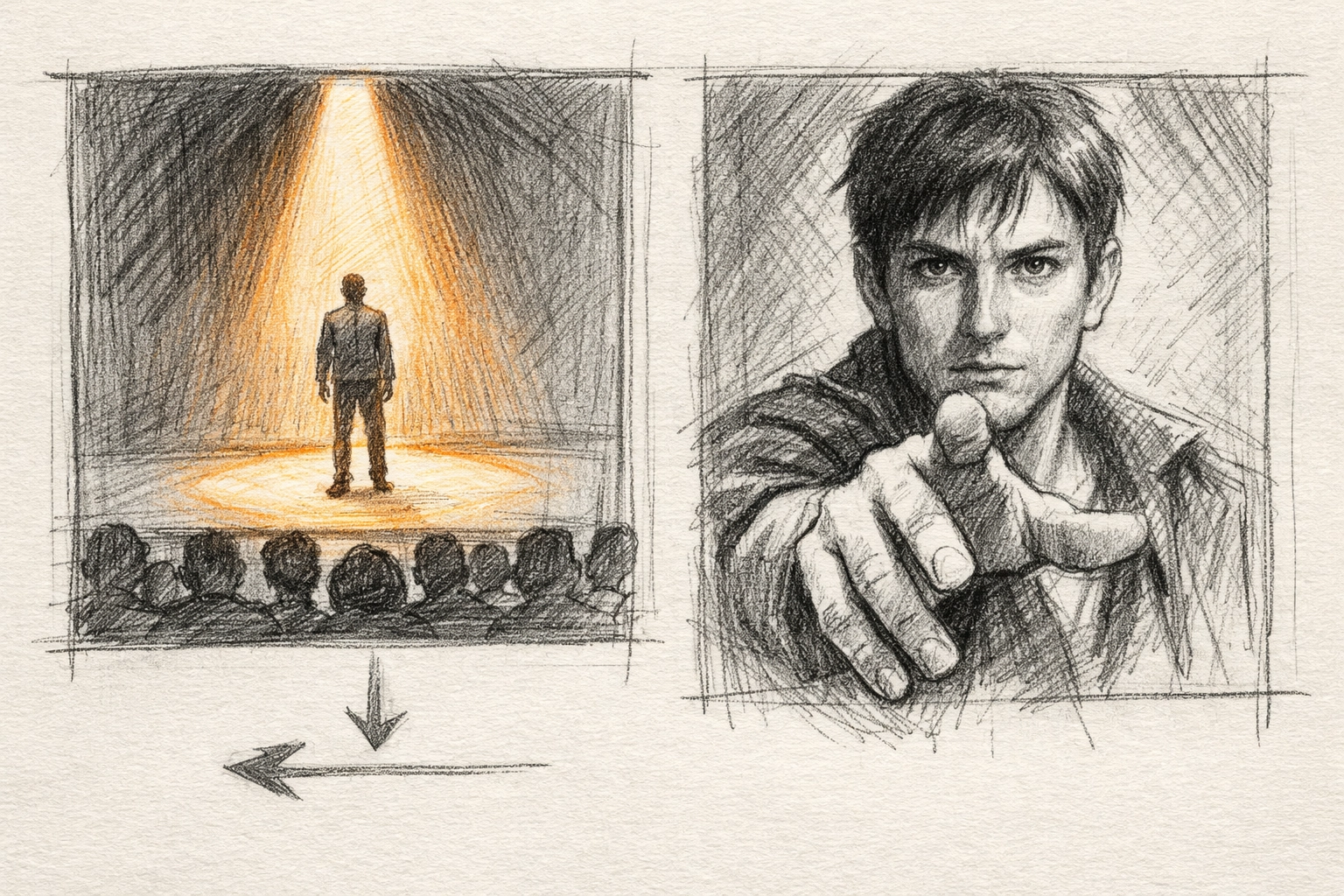

There's a moment in theater that nothing else in storytelling quite replicates. The lights come up. An actor steps forward. And instead of pretending you're not there, they look right at you.

That's it. That's the whole trick. And it changes everything.

The direct address opening is one of the oldest tools in the playwright's kit: older than realism, older than the proscenium, older than most of what we think of as "modern" theater. And yet, when it works, it still feels like a secret being shared. A door opening. A hand extended.

So why does it work? And more importantly: how do you use it without it feeling like a gimmick?

The Contract

Every play makes a contract with its audience in the first few minutes. The question isn't whether you're setting terms: you are: but whether you're doing it consciously.

A direct address opening makes that contract explicit. When a character steps out of the action to speak to us, they're saying: Here are the rules of this world. Here's what I need from you. Here's what you can expect from me.

In Our Town, the Stage Manager tells us outright that we're in Grover's Corners, New Hampshire, and that he'll be our guide. In The Glass Menagerie, Tom warns us that this is a memory play, and memory takes liberties. In Richard III, a villain invites us to be his accomplices.

Each of these openings does something different. But they all do the same fundamental thing: they establish trust by acknowledging the artifice.

Here's the paradox: by breaking the fourth wall, you often make the story feel more real. The audience relaxes. They know where they stand. And that clarity creates the space for everything that follows.

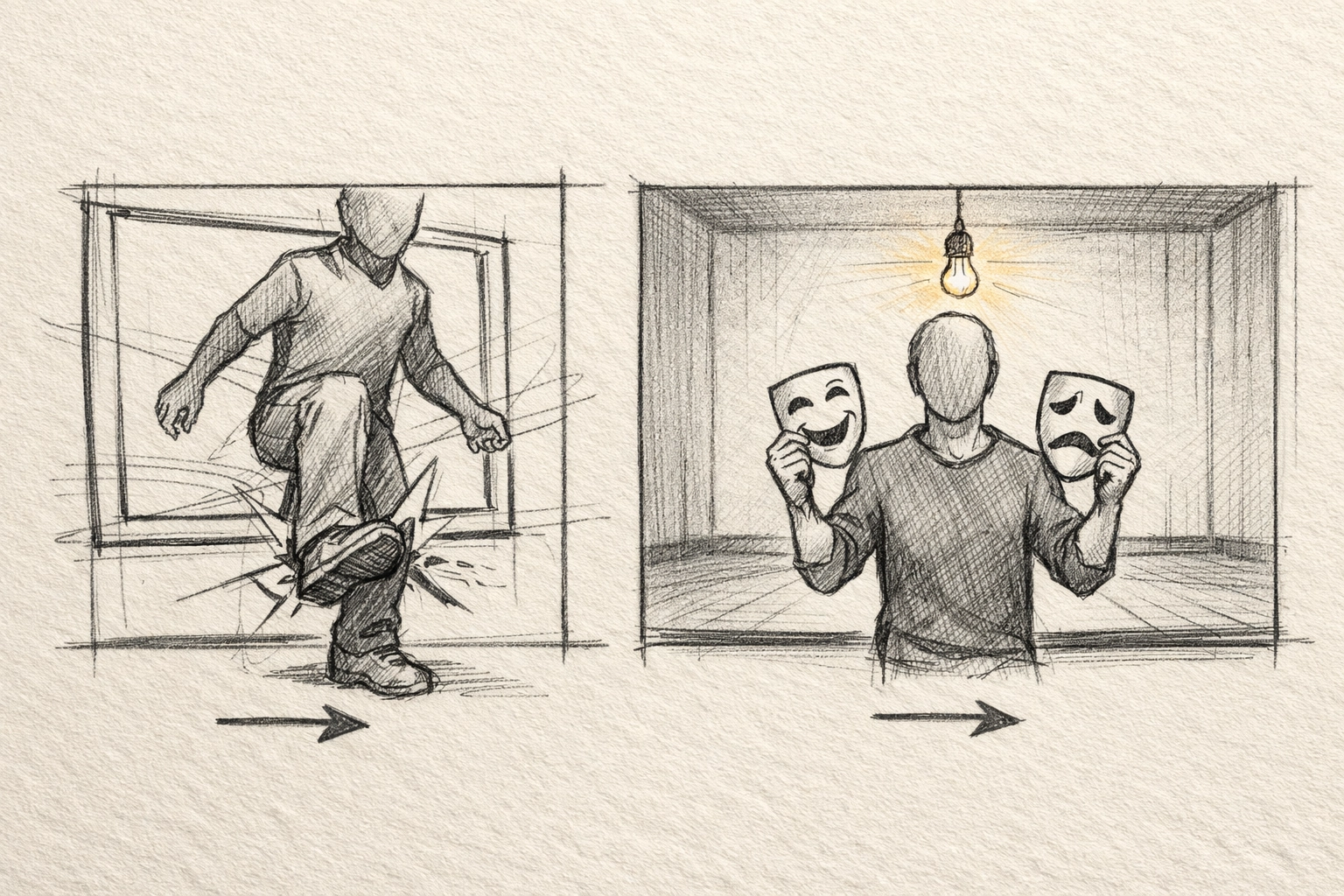

The Fourth Wall as a Tool

New writers sometimes treat the fourth wall like a sacred boundary: something you either respect or destroy. But the fourth wall isn't a wall. It's a dial. And direct address is one way to turn it.

The question isn't should I break it? It's what do I want the audience to feel when I do?

Direct address can create intimacy. When Vivian Bearing in Wit turns to us mid-diagnosis and walks us through her cancer treatment with academic precision and gallows humor, we're not just watching her: we're with her. The address makes us complicit in her survival.

It can also create manipulation. When Richard III opens with "Now is the winter of our discontent," he's not just setting the scene. He's seducing us. He knows he's the villain. He knows we know. And he's betting that if he lets us in on the joke, we'll root for him anyway.

That's the power of direct address: it can make an audience feel like a confidant or a co-conspirator. It can make them feel safe or deeply uncomfortable. It all depends on who's doing the talking: and why.

Four Flavors of Direct Address

Not all direct address openings are created equal. Over the years, a few distinct modes have emerged. Think of these less as rigid categories and more as starting points: ways to ask yourself what kind of relationship you want between your character and your audience.

Cinematic Deep Cuts (Universal Hat Tips)

Before we stay in play-land, a quick set of film hat tips: if you write for TV/film or you just like stealing tools across formats, direct address openings have a deep bench onscreen too: including some weirder, lesser-cited gems that show how elastic this move really is.

- Slacker (Richard Linklater): not a tidy "here’s the plot" opening so much as a roaming, hang-out handshake with the audience. It’s direct engagement without a traditional engine: the vibe itself is the contract.

- Funny Games (Michael Haneke): the chilling version. It’s direct address as manipulation: the film essentially recruits you, then punishes you for showing up. If you’re writing a "don’t trust me" narrator, this is a master class in weaponizing the look-to-camera.

- Symbiopsychotaxiplasm (William Greaves): a meta-documentary deep cut that complicates the whole idea of "Meta-Framing." You’re watching a film, about a film being made, about the people reacting to the film being made. The direct address isn’t a garnish: it’s the architecture.

- High Fidelity (Stephen Frears): a clean modern example of the "confessional best friend" version of direct address. It’s basically: I’m messy, let me explain myself, stay with me anyway.

- American Psycho (Mary Harron): if you want "Villainous Confidant" energy without the theatrical cape-swish, here it is: cool, curated intimacy that dares you to laugh and then makes you feel weird for laughing.

These aren’t "theater-but-on-camera." They’re reminders that direct address is a relationship tool, not a medium-specific trick.

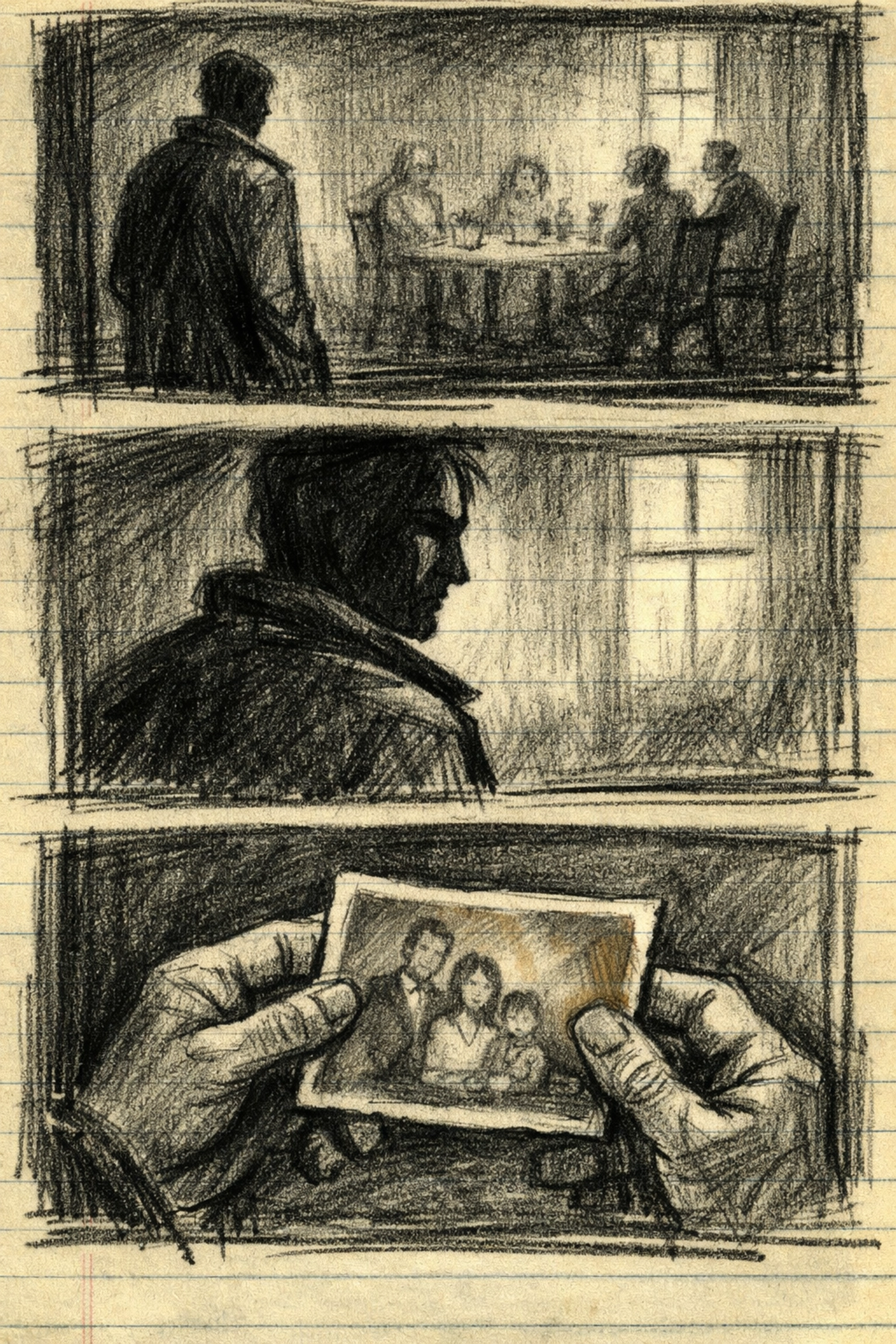

1. The Ghost (or the Memory)

"I am the narrator of my own haunting."

This is Tom Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie, standing outside the action, looking back. The Ghost isn't just telling us a story: they're processing it. There's distance between the speaker and the events, and that distance is the point.

The Ghost mode works when you want to foreground subjectivity. The audience understands from the jump that they're not getting objective truth. They're getting a truth, filtered through time and loss and longing.

Other examples: Dancing at Lughnasa, Lemon Sky, Faith Healer.

2. The Villainous Confidant

"I'm letting you in on the secret."

Richard III. Salieri in Amadeus. The villain who addresses the audience isn't confessing: they're recruiting.

This mode thrives on charisma and moral ambiguity. The character knows they're bad. They might even enjoy it. And by talking to us directly, they implicate us in their schemes. We become the only ones who know the full picture, and that knowledge is intoxicating.

The risk here is tipping into camp. The reward is an audience that can't look away.

3. The Meta-Framing

"This is a play, and we are here together."

Branden Jacobs-Jenkins opens An Octoroon by having a playwright named BJJ explain that he couldn't get a white director to direct his play about race, so he's doing it himself: and he's going to play multiple roles, including some in whiteface.

Heidi Schreck opens What the Constitution Means to Me by telling us she's about to recreate a speech she gave as a teenager, and that the structure of the evening will evolve as the play goes on.

The Meta-Framing mode doesn't just break the fourth wall: it examines the wall. It asks the audience to think about the act of watching, the politics of performance, the history of the form itself.

This is high-wire stuff. When it works, it's exhilarating. When it doesn't, it can feel like a lecture. The key is making the meta-commentary feel like something: not just mean something.

4. The World-Builder

"Here is how this universe works."

The Stage Manager in Our Town is the ur-example. He's not haunted. He's not manipulating us. He's not interrogating the form. He's simply explaining: this is the town, these are the people, here's what matters.

Danielle Dreilinger's Hurricane Diane opens with Dionysus: the god: addressing the audience and laying out the terms of the divine comedy to come. The tone is playful, the voice is authoritative, and the audience knows exactly what kind of ride they're in for.

The World-Builder works especially well in plays that create their own internal logic: magical realism, mythology, heightened worlds. The direct address becomes a kind of orientation, helping the audience get their footing before the strangeness begins.

A Note on Grief

One more thing worth mentioning: some of the most powerful direct address openings begin with loss.

Stephen Adly Guirgis opens The Last Days of Judas Iscariot with a mother's monologue about burying her son. It's raw. It's specific. And it sets the emotional stakes for everything that follows.

Direct address can be funny, charming, manipulative, disorienting. But it can also be an act of mourning. A character turning to the audience and saying: I need you to understand what happened. I need you to sit with this.

That kind of opening doesn't seduce. It demands. And when it works, it earns every second of attention that follows.

The Invitation

If you're a writer considering a direct address opening, here's the real question: What do you need the audience to feel before the story begins?

Do you need them to trust the narrator? Fear them? Question them? Do you need them to understand the rules of the world? Or do you need them to feel the weight of what's already been lost?

The direct address opening isn't a trick. It's an invitation. And like any invitation, it works best when you mean it.

So look them in the eye. Tell them why you brought them here. And then( only then( let the story begin.))

Leave a Reply