The Musical Engine: Why Your Script Needs a "Song" (Even if No One is Singing)

Here's a thought that might be controversial: we think every writer: whether you're crafting a gritty TV pilot, an indie film, or a three-character chamber play: should study musical theater structure.

Not because you need to write musicals. But because musical theater has solved problems that the rest of us are still fumbling around in the dark trying to figure out.

Why? Because musicals have to be ruthlessly efficient. You've got maybe two and a half hours, a dozen songs, and you need to establish a world, introduce a community, create a protagonist the audience will follow anywhere, build to an emotional crescendo, and stick the landing. There's no room for bloat. Every moment has to earn its place.

The principles that make a musical work are the same principles that make any story work. Musicals just make them visible.

So let's steal from them.

The "I Want" Song: Your Character's Engine

Every musical worth its Playbill has an "I Want" song. It's the moment, usually early in Act One, where the protagonist tells the audience exactly what they're chasing. Ariel wants to be part of that world. Eliza Doolittle wants a room somewhere. Seymour wants to get the hell out of Skid Row.

This isn't just a nice-to-have. It's the engine of the entire show.

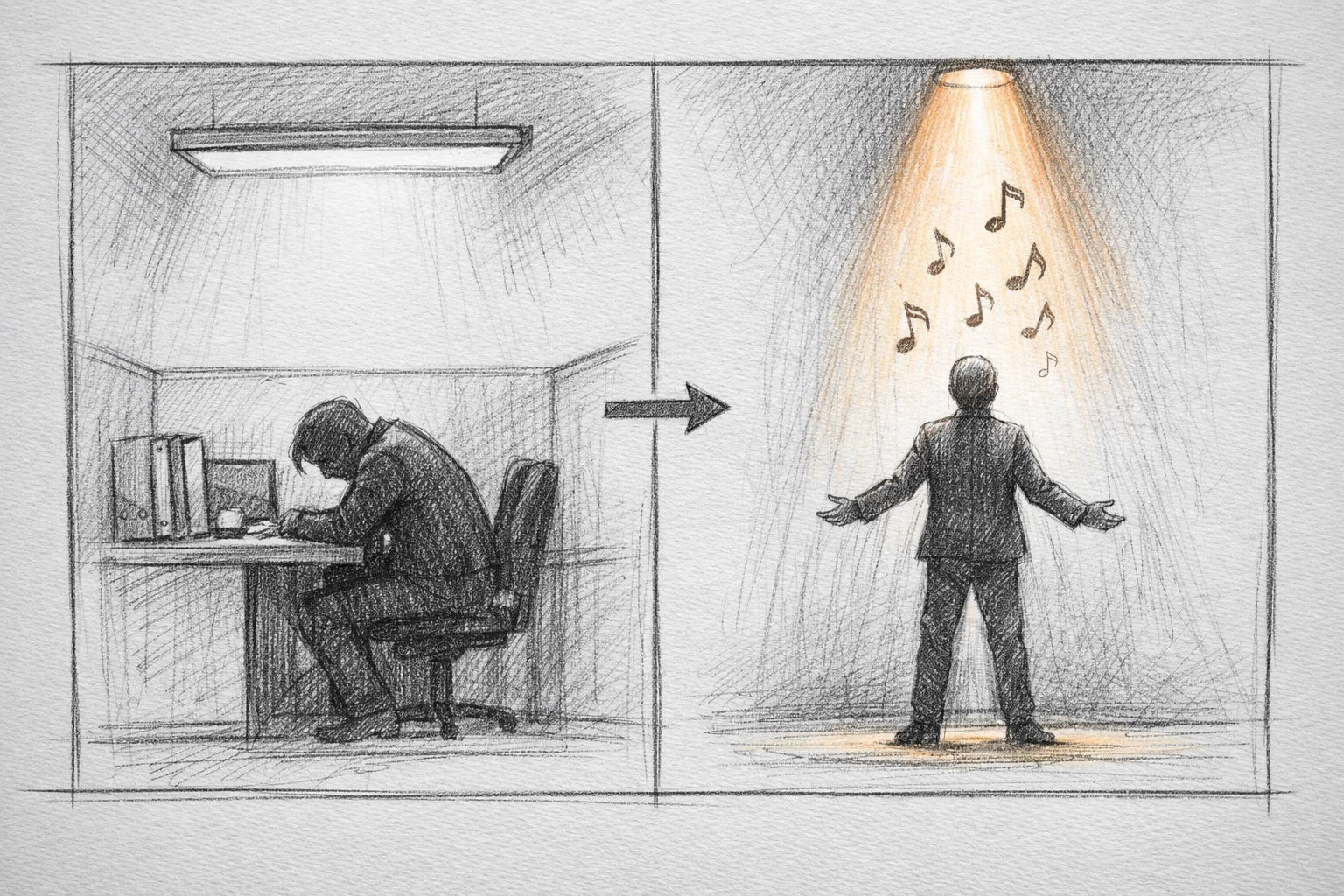

The "I Want" song does two things simultaneously: it tells us who the character is right now, and it tells us who they want to be. The gap between those two things is your story. Every scene that follows is either closing that gap or making it wider.

Now, your prestige drama doesn't have a literal "I Want" song. But it needs an "I Want" scene.

Think about Walter White cooking meth in his underwear: we know exactly what he wants (control, legacy, to stop being invisible) even before he says it. Think about the opening of Fleabag, where Phoebe Waller-Bridge breaks the fourth wall to tell us she knows what she's doing is a little messed up: we understand her desire to be seen, to be known, even as she hides.

The "I Want" doesn't have to be a monologue. It can be a look. A choice. A juxtaposition. But if your audience gets to page 20 and they don't know what your protagonist is reaching for, you've lost them.

The test: Can you articulate your protagonist's "I Want" in a single sentence? If you can't, neither can your audience.

The Opening Number: Building Your World in Five Minutes

One of the great crimes of contemporary screenwriting is the slow, atmospheric opening that takes fifteen minutes to "set the mood." Musicals don't have that luxury. They have to establish the world, the rules, the community, and the stakes in a single opening number.

Watch the opening of Fiddler on the Roof. "Tradition" isn't just a banger: it's a masterclass in efficient world-building. In under five minutes, you understand:

- The social structure of Anatevka (the papas, the mamas, the sons, the daughters)

- The precarious balance the community maintains

- The threat to that balance (the outside world pressing in)

- Tevye's role as both participant and commentator

Or look at "Belle" from Beauty and the Beast. In one number, you know that Belle is an outsider, the town thinks she's odd, she wants adventure, and Gaston is a problem. That's your entire first act setup, delivered in four minutes with a catchy melody.

Your film or play needs an "Opening Number" too: not a literal song, but a sequence that does the same work. The opening of Get Out (Chris preparing to visit Rose's family, the tension of a Black man in a white neighborhood) is an "Opening Number." The cold open of a great TV pilot is an "Opening Number."

The question to ask: Does my opening sequence establish the world, introduce the community, and hint at the threat: all before we've settled into the "normal" story?

The Eleven O'Clock Number: When the Truth Explodes

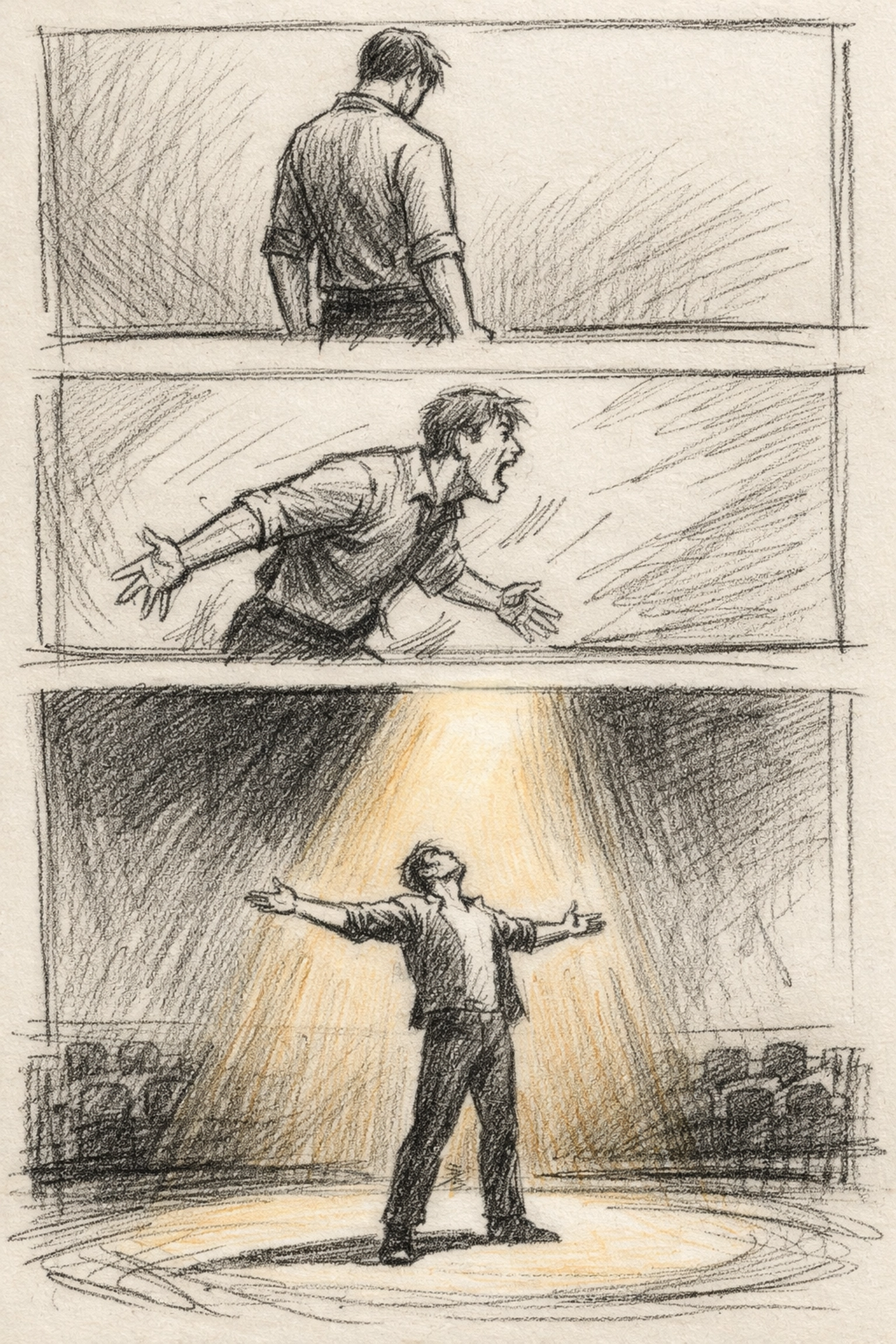

In musical theater, the "Eleven O'Clock Number" is the late-Act-Two showstopper. It's the moment where the protagonist can no longer contain their internal truth. The mask comes off. The subtext becomes text. The emotional stakes that have been building for ninety minutes finally detonate.

Think of Rose's "Rose's Turn" in Gypsy: the moment where a lifetime of suppressed ambition and resentment comes pouring out in a desperate, almost unhinged performance for an empty theater.

In non-musicals, this is your "Oscar Clip" moment. It's the scene that actors build their entire performance toward. It's the confrontation, the confession, the breakdown.

But here's what musicals understand that other forms sometimes forget: the Eleven O'Clock Number only works if you've earned it. You can't just drop a big emotional scene into your third act and expect it to land. The pressure has to build. The character has to resist their own truth for as long as possible. And then, finally, when they can't hold it in anymore, it explodes.

If your script has a big emotional climax that feels flat, the problem probably isn't the scene itself. The problem is that you didn't build the pressure cooker correctly in Acts One and Two.

Heightened Reality: Why Do They Sing?

Here's the question that people who hate musicals always ask: "Why do they suddenly start singing? It's so unrealistic!"

The answer is simple: because words aren't enough.

Characters in musicals sing when the emotion becomes too big for speech. When mere dialogue can't contain what they're feeling. The song is a release valve for an overwhelming internal experience.

Your non-musical script needs these moments too. Not literal songs, but "Musical Moments": sequences where the storytelling shifts into a heightened register because ordinary realism can't capture what's happening inside the character.

This might be:

- A montage that compresses time and emotion

- A visual sequence with minimal dialogue

- A poetic monologue that breaks from naturalistic speech

- A dream sequence or fantasy

- A moment of pure cinematic language: camera movement, music, editing: that does what dialogue cannot

The "Married Life" montage in Up is a Musical Moment. The "Layla" sequence in Goodfellas is a Musical Moment. The final monologue in The Glass Menagerie is a Musical Moment.

The principle: Identify the moments in your script where the emotion is bigger than the words. Then give yourself permission to go somewhere else: somewhere heightened, poetic, cinematic. Let the form bend to the feeling.

Simple + Simple = Complex

One of the smartest pieces of advice from musical theater composers is this formula: Simple music + simple lyrics = complex emotional experience.

This is counterintuitive. We often think that complex emotions require complex expression. But the opposite is true. When the music is simple and the words are simple, the audience has room to bring their own complexity to the experience. The song becomes a vessel for their feelings.

This applies directly to dialogue. The most devastating lines in dramatic writing are almost always simple. "After all this time?" "Always." That's it. That's the whole thing. And it destroys us.

If your dialogue is working too hard: if it's overwritten, over-explained, too clever by half: try stripping it back. Trust the structure you've built. Trust the actor. Trust the audience.

Your Script's Hidden Soundtrack

Every script has a rhythm, whether you've consciously designed it or not. The question is whether that rhythm is working for your story or against it.

Musical theater just makes the rhythm explicit. It gives us a vocabulary for things that all stories need: the engine of desire, the establishment of world, the building pressure, the emotional release, the moments where language fails and something else takes over.

You don't have to write a musical. But you might want to think like someone who does.

The Orchard Project supports writers across forms as they develop new work. If you're interested in our development programs, we'd love to hear from you.

Leave a Reply