Two Sides of the Same Heart: The Power of Split-POV Storytelling

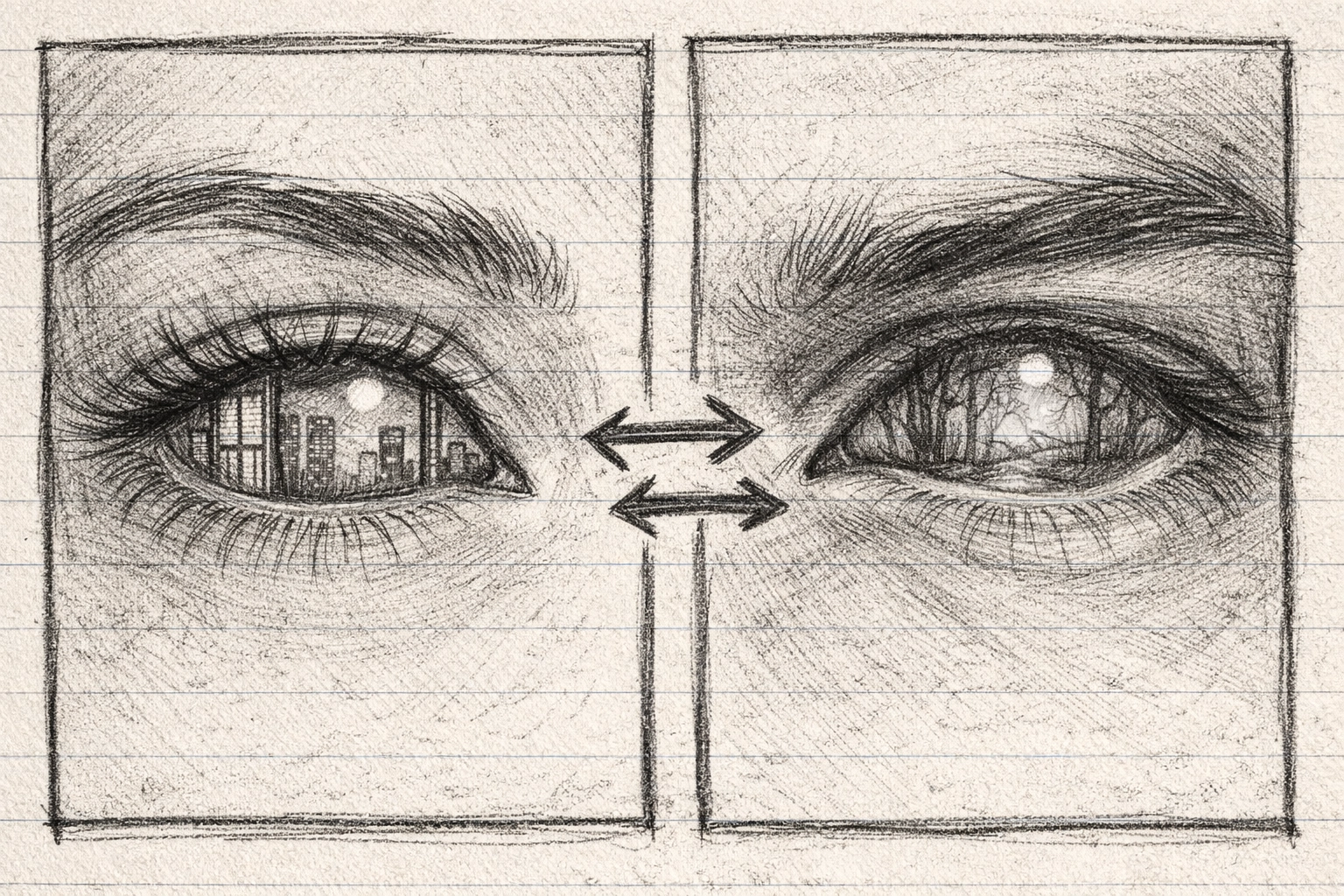

Split-POV stories are catnip because they admit what most narratives politely ignore: two people can live through the same event and come out holding different receipts.

It’s not just a “cool structure.” It’s a philosophy. Split-POV says truth is partial, memory is biased, and love is often a negotiation between two narrators who both believe they’re being fair.

And if you’re writing one, here’s the opinionated take: the goal isn’t to prove who’s right. The goal is to create a pressure system where the audience can’t stop comparing, correcting, and completing the story.

Love Is Never One Story

Here's a truth that most traditional narratives don't want to admit: love is not a single story. It's two overlapping narratives that rarely agree.

You remember the first time you met. Your partner remembers something completely different. You think the fight started when they said that thing. They're certain it started an hour earlier, when you didn't say anything at all. Neither of you is lying. You're just living in parallel realities that occasionally brush against each other.

Split-POV storytelling doesn't just acknowledge this truth: it makes it the engine of the entire narrative. And in doing so, it offers something that single-perspective stories can't: the space for audiences to build their own understanding in the gap between two versions of the same event.

The Third Narrative

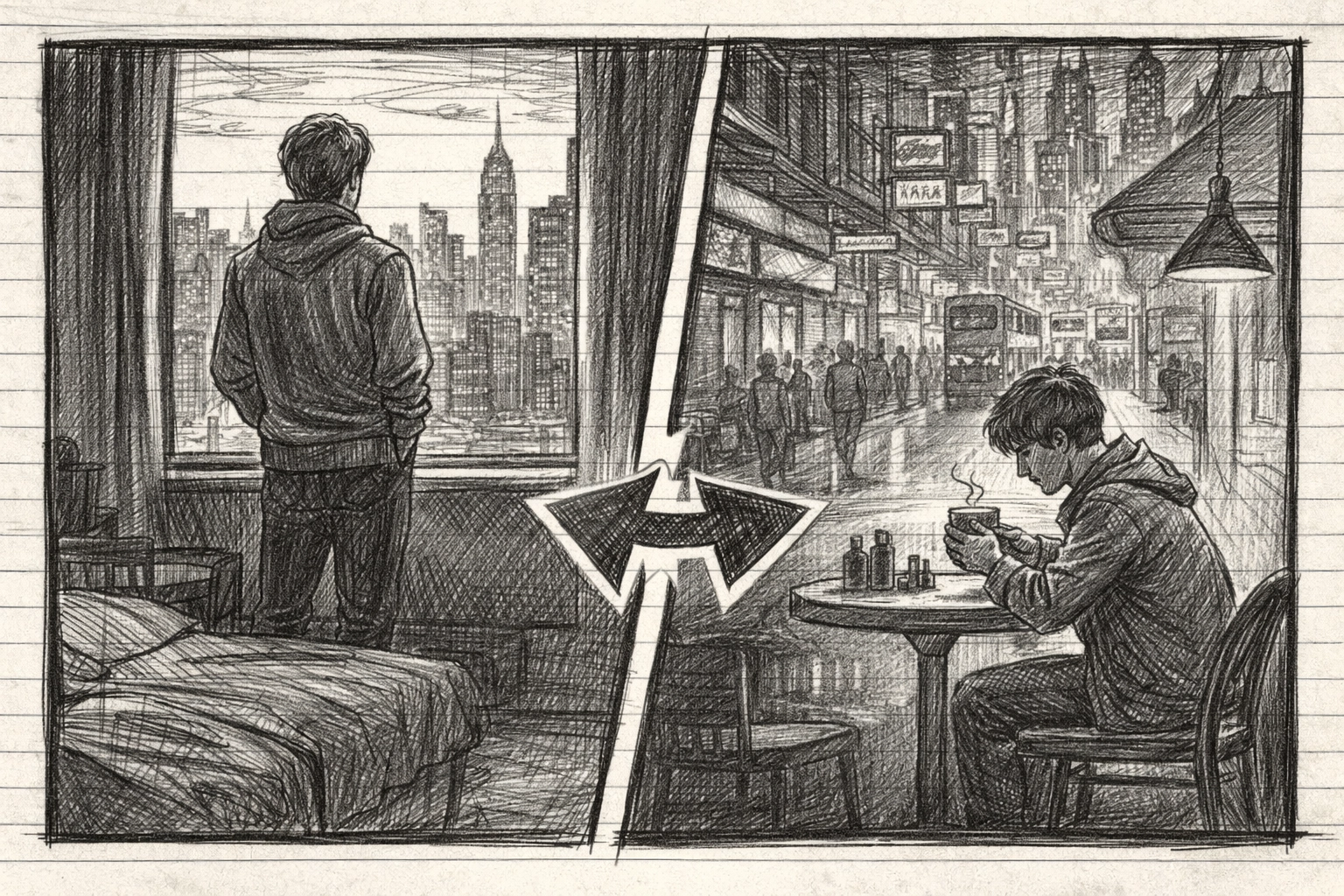

Here’s another people miss when they talk about “two perspectives”: split-POV isn’t two stories. It’s three.

- Character A’s version

- Character B’s version

- And the audience’s version, built out of friction, overlap, and omission

That last one is the point. Split-POV quietly assigns the audience a job: synthesize. Not “choose a side,” not “spot the plot twist,” but actively assemble a third narrative that feels truer than either single account.

This is why Rashomon still eats. It’s not just “different witnesses contradict each other.” It’s the craft of making each telling persuasive in its own emotional logic—and then forcing you to live in the discomfort of not being able to un-know any of them. The audience becomes the court, and the verdict is: truth is a construction.

Jason Robert Brown’s The Last Five Years pulls the same trick with time instead of testimony. Jamie moves forward. Cathy moves backward. They only occupy the same moment once. The result isn’t a puzzle; it’s an argument about how two people can narrate the same marriage as entirely different genres. One experiences momentum. The other experiences aftermath. And you, sitting in the dark, do the only humane thing available: hold both.

That third narrative—the one you build yourself—is where the actual dramatic labor happens.

A Working Taxonomy of Split-POV (Because “It Has Two Leads” Isn’t a Structure)

People throw “split-POV” around like it just means “we sometimes cut to the other person.” No. Split-POV is a design choice with rules, expectations, and specific payoffs.

Here are four buckets that are actually useful in the room when you’re building (or diagnosing) a draft:

1) The Mirror (divergent memories)

This is the Rashomon engine: the same event, multiple tellings, each warped by fear, pride, desire, self-protection, or plain confusion.

Modern relationship variants (like The Affair) do a great job with the micro-details: what someone was wearing, how long a pause lasted, whether a touch felt welcome or threatening. Those details aren’t trivia—they’re character. In Mirror stories, contradiction is characterization.

Cinematic Deep Cuts: The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby (the Him/Her versions) is a super clean example for theatre makers and screenwriters because it’s basically “same relationship, two interiors,” and the cut itself becomes the thesis. (Also: if you’re the kind of writer who likes building a draft by writing two monologues that argue with each other? This is your movie.)

Craft note: don’t write two “objective” versions and sprinkle tiny differences. Make each version emotionally inevitable to the person telling it.

2) The Clock (divergent timelines)

The split isn’t what happened—it’s when we’re allowed to know it.

The Last Five Years is the cleanest demonstration of this: two opposing vectors, one relationship, one collision point. You can add other timeline-y cousins here for technical satisfaction: 500 Days of Summer isn’t strictly two POVs, but it behaves like a Clock story in its editorial grammar—constantly revising our read of the relationship by reordering the evidence.

Cinematic Deep Cuts: Gus Van Sant’s Elephant is a devastating Clock variant: it loops time to track multiple students as their paths overlap through the same day. Same building, different coordinates. The repetition isn’t redundancy—it’s dread. (And if you’re writing for the stage: it’s a great reminder that re-entering a moment from a new angle can be more suspenseful than “moving forward.”)

Craft note: Clock narratives thrive on contrast at the seam. Put scenes next to each other that are emotionally adjacent even if temporally distant.

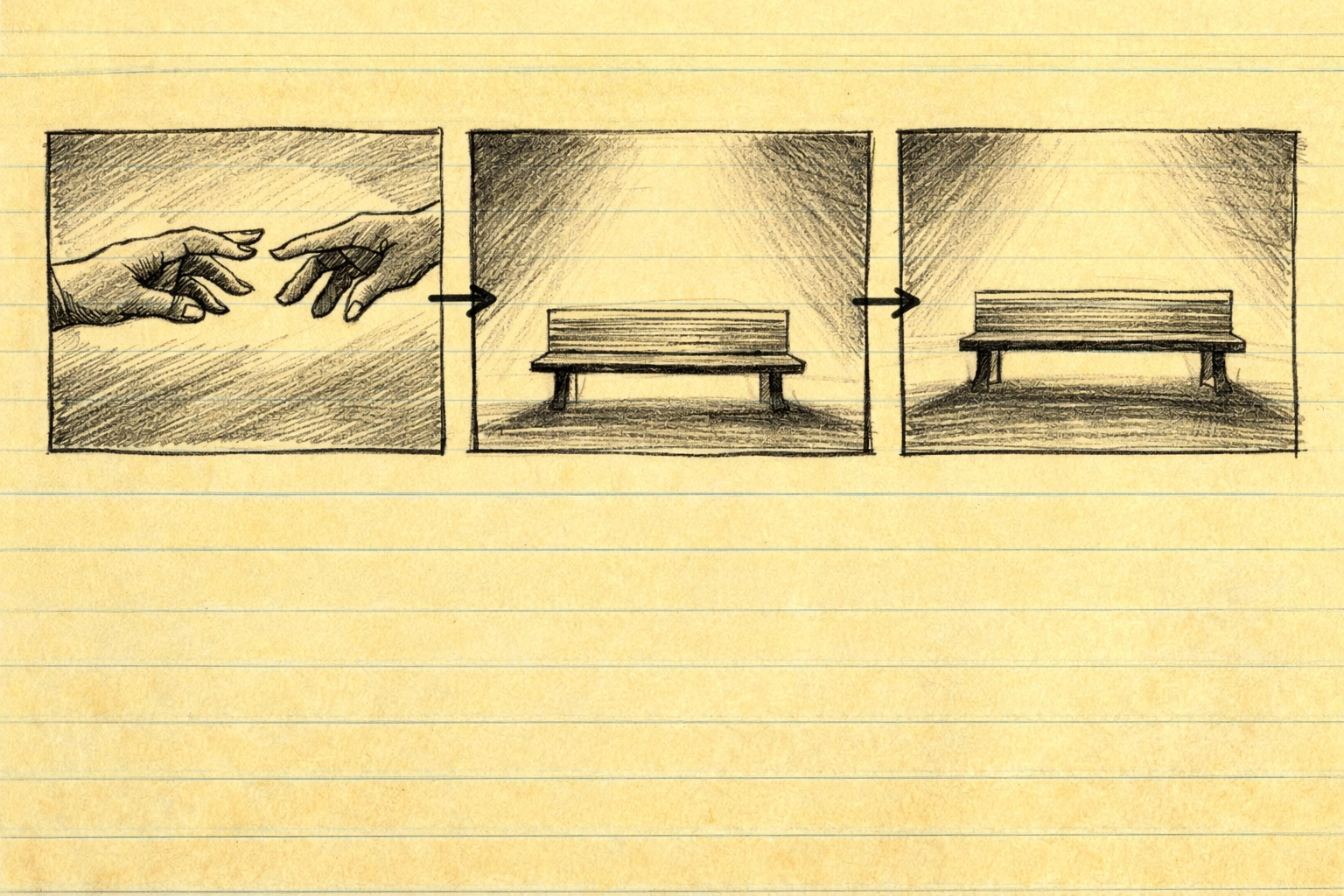

3) The Parallel (separate lives moving toward a collision)

This is the “two tracks” structure: separate protagonists, separate daily realities, with the audience doing the math of inevitability.

Sleepless in Seattle is the pop template. But the deeper version is something like Comrades: Almost a Love Story, where coincidence, migration, and economics become the rails that guide two lives toward (and away from) each other. Parallel stories are romantic precisely because they make fate feel like urban planning.

Also: if you want a masterclass in parallel longing, look at Makoto Shinkai’s 5 Centimeters per Second. It’s basically a film about two narratives that can’t quite synchronize—distance as structure.

Cinematic Deep Cuts: Mike Figgis’s Timecode is the ultimate four-way split-screen flex: four continuous takes running simultaneously. It’s not “two tracks,” it’s a whole switchyard. For screenwriters it’s a reminder that parallel structure can be literal in the frame; for theatre makers it’s basically a proof-of-concept for simultaneity—multiple scenes happening at once, with the audience choosing what to privilege.

Craft note: Parallel stories need a shared object / shared song / shared place that functions like a magnet. Without that, you’re just cross-cutting.

4) The Twist (perspective shift that re-frames the first half)

This is the sharpest tool and the easiest to misuse. The perspective shift isn’t “surprise!”—it’s a reallocation of empathy and power.

The Handmaiden does it with glee: the same sequence becomes a different moral universe once you swap whose interiority we’re inside. Gone Girl turns the perspective shift into a weapon: it changes what kind of story we thought we were watching.

Cinematic Deep Cuts: the French indie À la folie… pas du tout (He Loves Me… He Loves Me Not) pulls a radical mid-film perspective flip that’s basically a clinic in re-framing. It’s not just “now we see the other side”—it’s “oh, we’ve been in the wrong genre.” If you’re building a Twist split-POV, this is a great north star: the second perspective doesn’t add trivia, it rewrites meaning.

Craft note: if the twist only works because you hid information the POV character would reasonably have, it’s not a Twist—it’s a cheat.

The Tension of Dramatic Irony

Split-POV also unlocks a specific kind of tension that single-perspective narratives struggle to achieve: the ache of knowing something a character doesn't.

And yes, we are going to say the quiet part out loud: split-POV is an empathy machine only if you let it stay unresolved. The moment you turn it into a courtroom where the writer hands down the “right” account, you’ve undercut the whole form.

In Celine Song's Past Lives, we follow Nora and Hae Sung across decades: childhood friends in Seoul, reconnecting briefly in their twenties, finally meeting in person in their late thirties. The film isn't strictly split-POV in a structural sense, but it operates in that emotional register. We see Nora building a life in New York. We see Hae Sung waiting. We understand things neither of them can fully articulate to each other, and that understanding is where the heartbreak lives.

Makoto Shinkai's anime Your Name takes this even further with its body-swapping premise. Two teenagers wake up in each other's lives, leaving notes and messages, slowly falling for someone they've never technically met. The audience holds both timelines, both sets of memories, both dawning realizations: and we feel the pull between them precisely because we can see what they can't.

This is dramatic irony in its purest form. Not irony as cleverness, but irony as compassion. We know more than the characters, and that knowledge makes us ache for them.

Why This Matters for the Story Economy

In an earlier post, we wrote about what we've been calling the story economy: the idea that we live inside competing narratives, and that the stories which circulate most freely often aren't the most accurate or humane, but the most emotionally efficient. Simple. Fast. Clear villains and heroes.

Split-POV storytelling is, in some ways, a direct counter to that efficiency. It insists on complication. It refuses the single, clean truth. It asks audiences to do work: to hold contradictions, to resist easy judgments, to sit in the discomfort of not knowing whose side to take.

And in a cultural moment where narratives are weaponized daily, that skill matters. The ability to hold two versions of a story without collapsing into certainty is a kind of civic muscle. Art that exercises it: that trains us in ambiguity: isn't just entertainment. It's practice for living in a complex world.

A Quick Canon (If You're Looking)

A short starter kit, organized by what it’s doing (not just what it’s about):

- The Mirror: Rashomon – divergent memories as moral battleground

- The Clock: The Last Five Years – two timelines, one relationship; 500 Days of Summer – editorial time as argument

- The Parallel: Sleepless in Seattle – converging tracks; Comrades: Almost a Love Story – parallel lives shaped by place and chance; 5 Centimeters per Second – parallel longing that can’t quite sync

- The Twist: The Handmaiden – perspective as reframe; Gone Girl – perspective as weapon

- For technical satisfaction: The Rules of Attraction – multiple POV passes that reveal how social reality is basically a broken telephone

Each of these understands something essential: split-POV isn’t about “seeing both sides.” It’s about watching the audience build a third story out of two incomplete truths.

The Invitation

If you're developing work right now: a play, a film, a musical, whatever: consider what perspective is doing in your story. Not just who's talking, but whose version of events is being privileged. And ask yourself: what would happen if you split it? What would the audience learn by holding two incomplete truths?

The answer might just be the story you're actually trying to tell.

Leave a Reply