The “No-Budget” Spectacle: How to Write Big Ideas for Small Rooms

Here's the thing nobody tells you when you're starting out: spectacle doesn't live in the budget line. It lives in the idea.

I know that sounds like motivational poster nonsense, but stick with me. Because the best "big" theater I've ever seen, the kind that makes you feel like the walls disappeared and you're standing in the middle of something impossible, wasn't built on a Hollywood budget. It was built on a writer who understood that constraints aren't problems to solve. They're invitations to get weird.

The Trick Hidden in Plain Sight

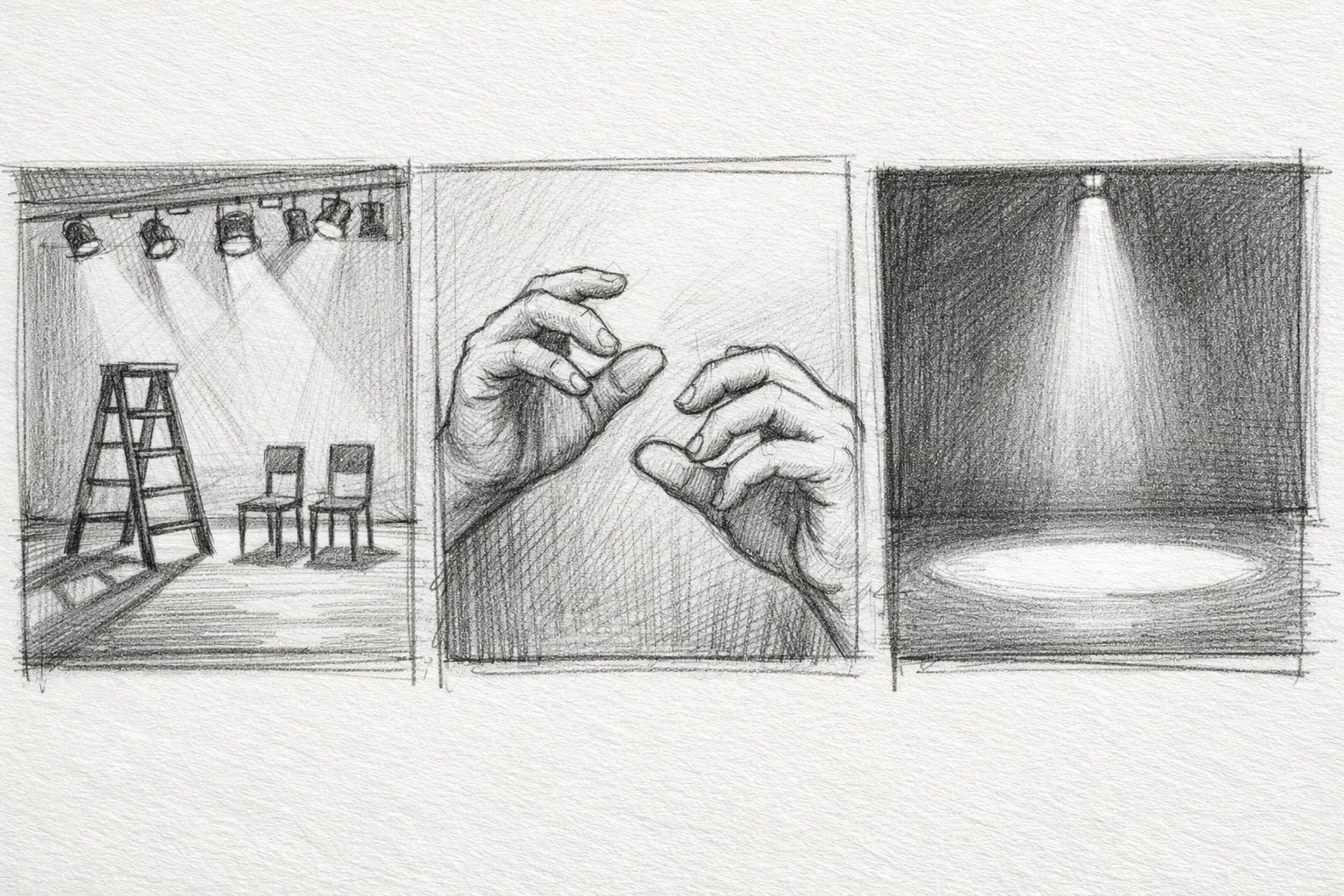

Let's start with the most famous example: Our Town. Thornton Wilder wrote a play about life, death, marriage, and the entire cosmos of a New Hampshire town using literally nothing. No set. No props (okay, some chairs and a stepladder, but you get it). The Stage Manager tells you what you're supposed to see, and your brain does the rest.

That's not "making do." That's a radical artistic choice. Wilder could have written detailed Victorian interiors and bustling street scenes. Instead, he wrote a play where the absence of stuff becomes the point. When Emily revisits her twelfth birthday in Act Three, the lack of physical detail makes her emotional devastation hit harder. We're not distracted by period-accurate wallpaper. We're watching a soul realize what she's lost.

Same energy, different century: Hamilton. Lin-Manuel Miranda didn't write "we can't afford a boat, so let's just… not show the boat." He wrote a play where movement IS the spectacle. The turntable isn't a gimmick, it's built into the structure. "My Shot" doesn't need a set change because the choreography creates the revolution. The brick wall stays. The ideas move.

When Budget Becomes Concept

Now let's get weird.

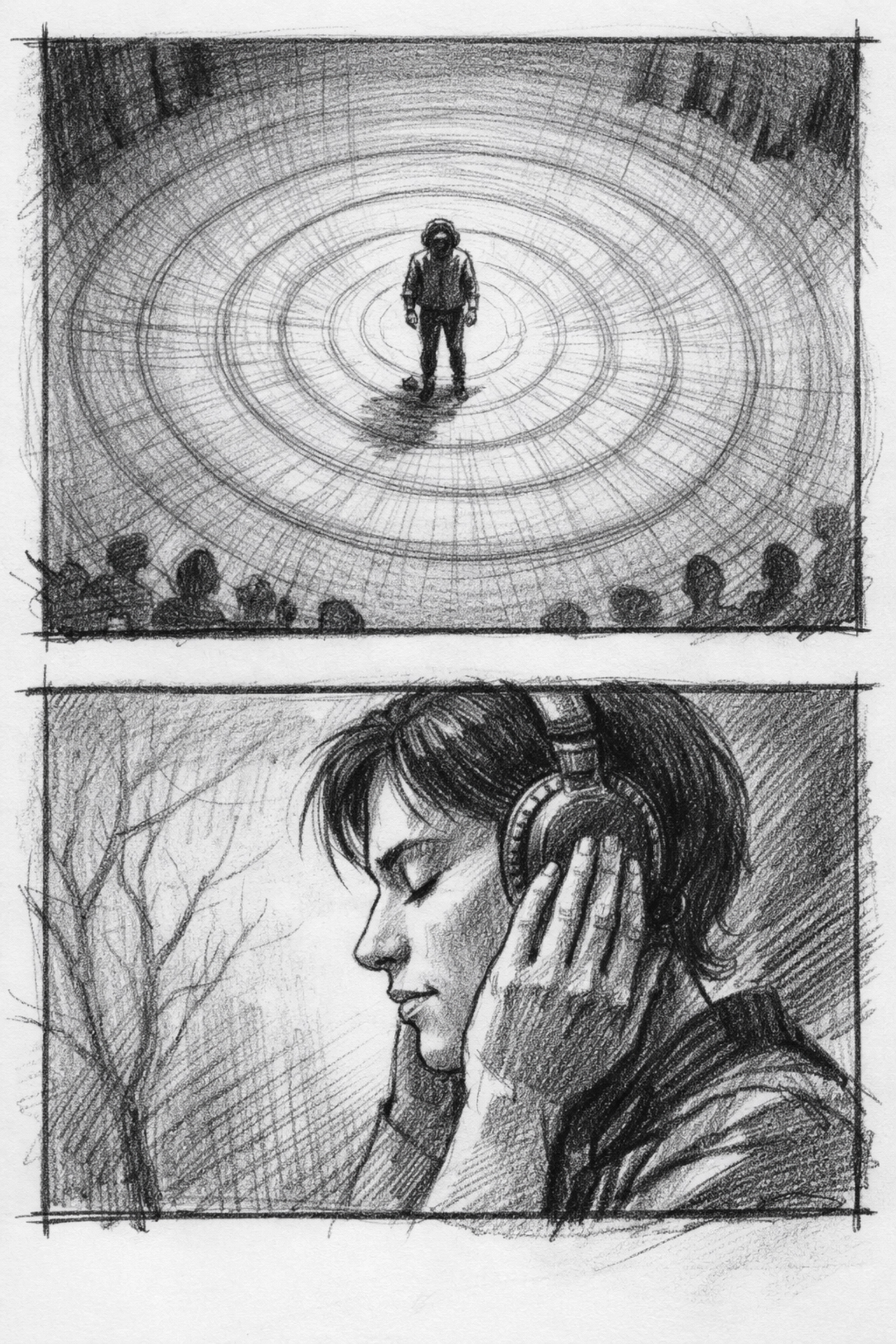

Simon McBurney's The Encounter is a solo show about a National Geographic photographer lost in the Amazon rainforest. One actor. Minimal set. And it's one of the most immersive pieces of theater you'll ever experience, because McBurney wrote for binaural audio. The audience wears headphones. The jungle happens in your skull. Rain. Insects. Voices circling your head. The "spectacle" is neurological.

That's not a production choice bolted onto a script. That's a writer who thought: What if the technology IS the storytelling? McBurney didn't write around the limitation of one performer. He wrote INTO the intimacy of being alone inside someone else's head.

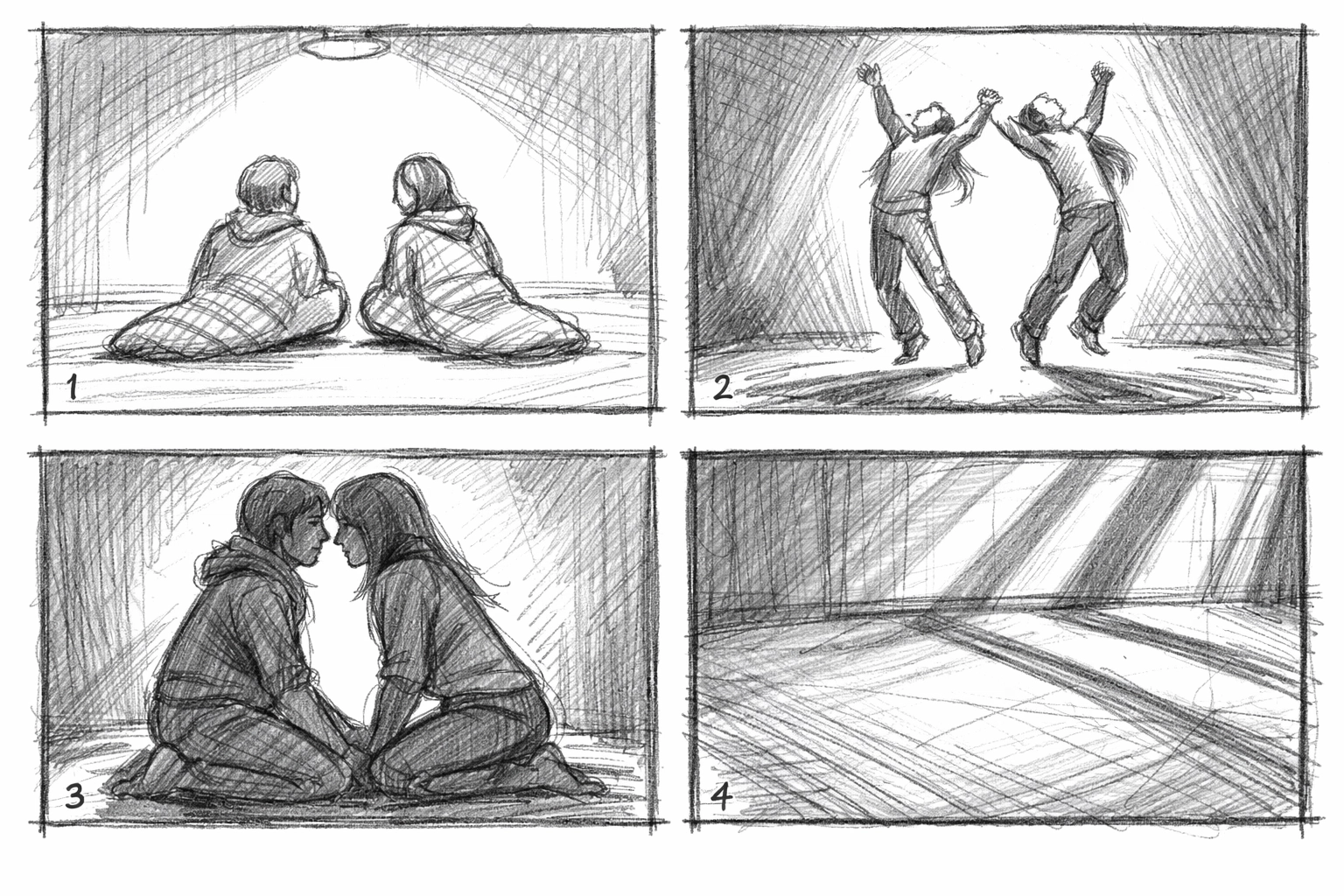

Or take Bess Wohl's Small Mouth Sounds. It's set at a silent retreat. Almost no dialogue. Just five strangers trying not to talk for a weekend while their inner chaos leaks out in glances, suppressed laughter, and the ambient sound of nature. Wohl took a "no-budget" constraint, what if we barely use language?, and made it the whole point. The silence becomes louder than shouting.

How to Actually Write This Way

Okay, so how do you DO this? How do you sit down at your desk and write a play that feels massive when you know it's going to be performed in a black box with four light cues?

1. Pick One Impossible Thing and Make It the Engine

Don't try to write a "small" play. Write a play with one conceptually huge idea and then figure out the cheapest, most elegant way to stage it.

Want to write about space travel? Don't write a spaceship. Write two astronauts in sleeping bags on the floor, staring up, describing what they see. The audience will put the stars there. (See: The Effect by Lucy Prebble, which stages a pharmaceutical trial in a stark white room and makes you feel the brain chemistry shifting.)

Want to write about a revolution? Don't write crowd scenes. Write one person remembering a crowd. Or two people becoming a crowd through movement. Or silence where the crowd should be.

2. Write Active Minimalism, Not Passive Poverty

There's a difference between "we couldn't afford the prop so we cut it" and "the absence of the prop is doing dramatic work."

In Our Town, the missing props aren't invisible. They're LOUD. When Emily pantomimes stringing beans, you see her hands. You see the beans. You see the kitchen. The absence is active. It asks you to participate.

If you write a scene where a character says, "Look at this beautiful vase," and there's no vase… that's poverty. If you write a scene where a character says, "There used to be a vase here," and the empty space becomes a ghost, a history, a rupture, now you're writing.

3. Use Sound and Rhythm as Architecture

The cheapest spectacle is sonic. You can create an entire world with overlapping voices, silence, a repeated phrase, or a rhythm that escalates.

Small Mouth Sounds uses the ambient sounds of nature (birdsong, wind, distant thunder) to create pressure. The environment becomes a character without a single set piece.

The Encounter uses stereo sound to put the Amazon in your ears, footsteps circling you, water dripping behind your left shoulder, a voice that sounds like it's coming from inside your own thoughts.

When you're writing, think: What does this moment sound like? Can you create scale through echo? Through overlap? Through the sudden absence of noise?

4. Write Transformations, Not Locations

In low-budget theater, you can't build ten different sets. But you CAN write ten different emotional states in the same physical space.

The genius of something like Angels in America (which, yes, has big moments, but also played in tiny spaces early on) is that Kushner writes transformations. Prior's hospital room becomes Heaven. The Bethesda Fountain becomes a cosmic threshold. It's not about moving scenery: it's about the language and the stakes shifting so dramatically that the space itself seems to change.

Write the transformation. Let the director figure out the light cue.

The Real Spectacle Is Permission

Here's what I think is actually happening when we talk about "big ideas in small rooms":

We're not talking about making do. We're talking about giving the audience permission to imagine with you.

The commercial theater model trains us to expect everything pre-built. CGI waterfalls. Rotating chandeliers. But that's not why people come to theater. They come because a live person is standing in front of them, breathing the same air, making a choice in real time. That's the spectacle. The aliveness.

When you write for a small room, you're not asking for less. You're asking for more: from your actors, your audience, and yourself. You're saying: We're going to build this world together, right now, out of nothing but language and belief and presence.

That's not a limitation. That's the whole point.

A Final Thought (From One Writer to Another)

The next time you catch yourself thinking, "This idea is too big, I can't afford to stage it," stop.

Reframe: "This idea is too big to waste on literal representation. How do I write it so the audience has to meet me halfway?"

That's where the magic lives. Not in what you can afford to show: but in what you can afford to suggest, to imply, to whisper into being.

Our Town didn't need a set. It needed Wilder's guts to say: "You don't need to see Grover's Corners. You need to feel it."

You've got the guts. Now write the play.

Looking for more craft tools? Check out Episodic Engines or dive into The Musical Engine for structure ideas that work in any size room.

Leave a Reply